Advertisement

By some estimates, South Africa has a housing backlog of about 2.3 million, and that number grows by about 178,000 houses a year. Despite the country’s sophisticated banking system, busy property market, generous impact investment projects and advanced construction industry, neither the public nor private sector has been able to catch up that backlog.

Dire situation

A lot has been said and written about South Africa’s housing crisis, and about the affordable housing solutions (some successful, others not) that hope to solve it. But amid all the noise, there’s a bewildering lack of clarity about the extent of the problem, its causes, and the implications of leaving it unsolved.

In 2018, according to Statistics South Africa’s latest General Household Survey, some 81.1% of the country’s households lived in formal dwellings. But, while the percentage of households that have received some kind of government subsidy for RDP housing has increased from 5.6% in 2002 to 13.6% by 2018, there were still 13,1% of households living in informal dwellings. Dig deeper into the 2018 and 2017 surveys, and you find concerns raised by residents about the quality of those subsidised RDP houses: 10,2% of them said the walls were weak or very weak, while 9,9% rated the roofs of their dwellings as weak or very weak.

Despite putting a roof over the heads of 13.6% of South Africa’s households, the RDP programme has both failed to keep pace with demand, and failed to deliver quality affordable housing. The Department of Human Settlements has even rebranded the project, renaming the RDP housing plan ‘Breaking New Ground’ (BNG). According to public interest news site GroundUp, the Department ‘wants to integrate different types of housing – rented, bought and subsidised – and provide facilities like schools, clinics and shops, to improve the quality of people’s lives. BNG houses are supposed to be larger than RDP houses, with two bedrooms, a separate bathroom with a toilet, shower and hand basin, a combined kitchen and living room area, and electricity installation, where electricity supply is available in the township.’

Serious problem

But no matter how often you paint the walls or provide subsidies, the housing crisis ultimately boils down to affordability. Even with government subsidies, houses are simply too expensive for the vast majority of the population.

According to the South African Affordable Residential Developers Association (SAARDA), in 2018 the cheapest newly built house in South Africa cost about R352,500. ‘Under these terms, the house would be affordable to only 34.4% of urban households. Low household incomes, poor credit records limiting access to finance, rising building costs, and scarcity of affordable, well-located land for human settlements development are all factors that contribute to the affordability challenge,’ SAARDA said in a recent statement. Solving that problem on the supply side – as the government has attempted to do through its RPD/BNG subsidies – is clearly not working.

Advertisement

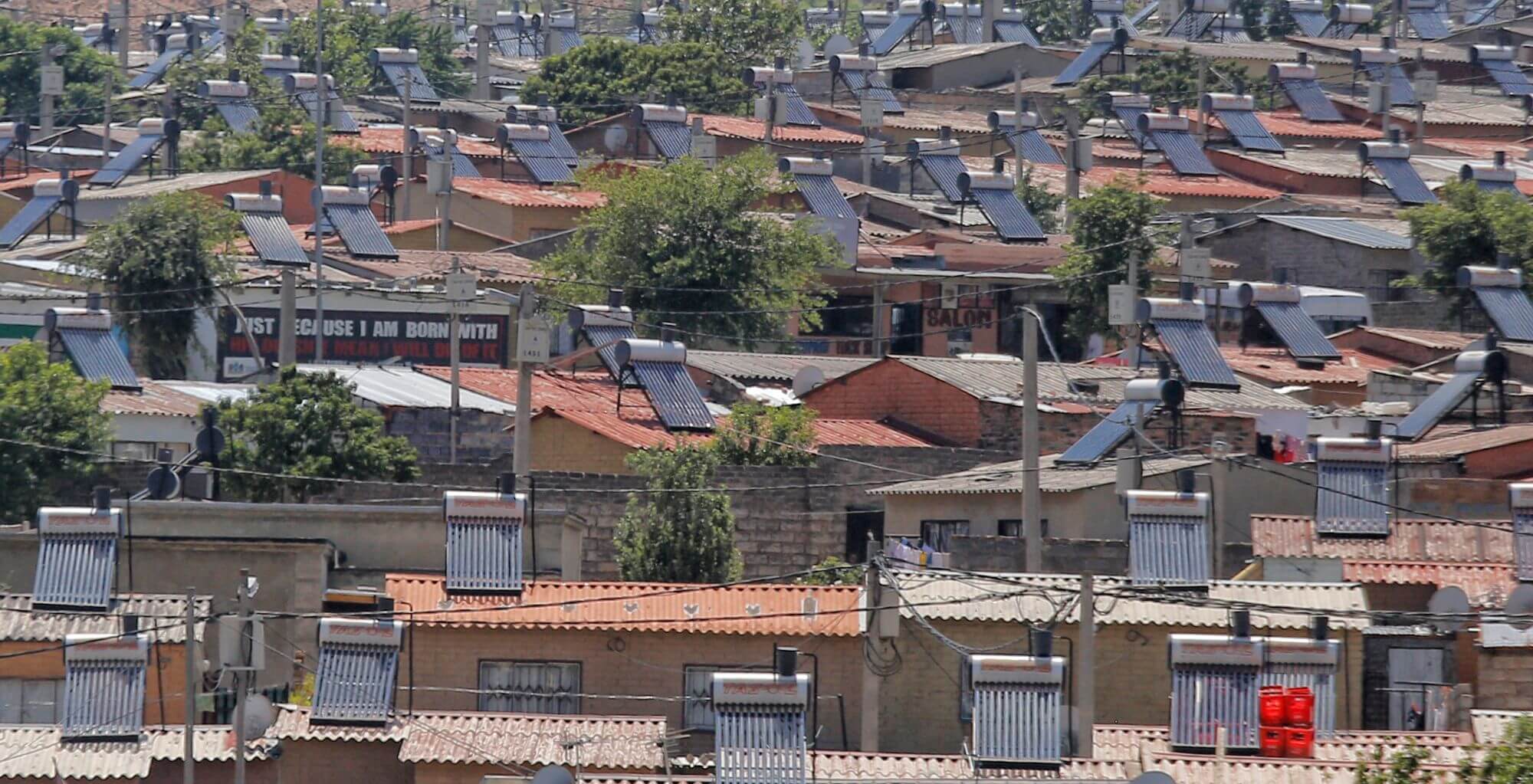

The result is hundreds of thousands of South Africans perpetually living in informal dwellings, at worst, or in rented housing at best. That rental market is a fertile ground for innovative solutions – especially in townships, where property entrepreneurs (called micro-developers) are building rental structures in their backyards. Given the opportunity, those developments can then scale up to multi-unit dwellings.

Some possible solutions

Soweto-based affordable housing business Hustlenomics is stepping into this space, training women and the youth to replace informal backyard shacks with durable structures. The idea is to provide formal buildings for low-income households who cannot access traditional home financing. The way it works is that once the formal structures are completed, Hustlenomics then splits the rental income with the landowner until the construction costs have been recovered, after which full ownership is handed over to the landowner. Hustlenomics won the SAB Foundation Social Innovation Award. In a statement after receiving the award, founder Nhlanhla Ndlovu explained: ‘We train women in our local community by teaching them how to manufacture sustainable bricks using sand and 10% cement. This method both costs less and is three times faster to manufacture. We also teach them to build sustainable houses using those bricks.’ He said he’d use his prize winnings to buy a brick-making machine that can produce up to 4,500 bricks a day.

Meanwhile, the Social Justice Coalition is taking a broader, systemic approach to the problem in its Land Tenure and Upgrading of Informal Settlement Programme (UISP). The SJC noted that many of South Africa’s long-established urban informal settlements are extremely densely populated, yet lacking in basic services – and the problem is only exacerbated by the legacy of apartheid spatial planning.

‘The government’s solutions to the housing crisis tend to be large-scale housing sites which are often located far from the communities and facilities currently in place within existing settlements,’ the SJC says. Its UISP takes an ‘in-situ’ approach, providing housing on the site of the existing settlement. This way, households no longer need to be relocated away from their existing communities and support structures. ‘In-situ upgrading is also supposed to improve residents’ tenure security, by giving residents the right to occupy and not be removed from the location where they live. They are therefore given security of tenure,’ the SJC explains.

The UISP aims to include communities in the upgrading process, thereby reducing the disruption and ensuring that the communities are involved in the upgrading of their areas. Upgrading is done in four stages, going through the incremental stages of community participation, supply of basic services, and tenure security.

The SJC’s approach involves a grand and ambitious vision – perhaps too ambitious. But the scale of South Africa’s housing crisis is such that opportunities have to be found where they can. If that means shifting focus from subsidised housing to more affordable rentals, then that may be where the Band-Aid needs to be applied for now.

It’s clear that a solution – any sustainable, lasting solution – is needed to the crisis. With 13,1% of our country’s households still living in informal dwellings, and with only 34.4% of urban households able to buy their own home, the numbers aren’t looking good.

Is this an opportunity?

Where there is a problem, there is often a solution. And where there is a solution, there is usually an opportunity. But the affordable housing crisis – particularly at the lower end of the spectrum – is one with no obvious solutions, and no fruity low-hanging opportunities. There are opportunities there, but they will require ingenuity and creativity, and a definite business not-as-usual approach. And isn’t that the definition of entrepreneurship?