Advertisement

Museums are not about old crockery, vintage clothes, beautiful furniture, historical photos and rusty farm implements. They’re about stories, but sometimes you have to look hard to find them. And sometimes those stories illustrate an important principle or moral.

Strolling down the Heerengracht on a beautiful sunny morning, tall, broad-shouldered Johannes Buyskes started at the sound of the Noon Gun, and then instinctively reached into his waistcoat to check the accuracy of his watch. As he returned the timepiece to his pocket, the unusual texture of the fob sent a chill down his spine. He would never forget that dark and stormy night.

He would never forget the booming thunder, the wild water with its terrifying flotsam – and the desperate screams that floated out above the shrieking wind. And Rainie Dodds the next morning, Ophelia-like, floating in the still, mudbrown pool downstream – her torn wedding dress caught on a thorn tree as she drifted in the eddy with her long hair forming a halo around her grazed and battered, once-beautiful face. He hadn’t been in time to save her; he didn’t even know her. And he had certainly been unaware that she was standing in front of her mirror trying on her wedding dress in joyful, girlish anticipation of her imminent marriage.

She smiled at her flickering, candle-lit reflection as she thought back to how her fiancé had kissed her that afternoon, whispering that soon she would be his wife. A wave of desire washed over her but, before she could be totally swept away, she was rudely brought back to reality by a sharp crack, followed by a spine-chilling scream and a roar that shook the foundations of the house. She jumped up and ran towards the door. Too late. She was swept away – but not by passion – by a towering pitch-black wall of water, rocks and logs that crashed into and through the house, and carried her downstream like a broken doll.

Advertisement

It was at about that moment that Johannes had arrived at the small town, tired, cold and hungry. He had been hoping for a hot meal, a drink and a good night’s sleep before delivering the mail in the morning, and then continuing on to the Diamond Fields. But when he heard the screams and the crashing, rock-filled torrent, he had urged the horses on for the final stretch into the town.

Forgetting his tiredness, he abandoned the mail coach and dashed into the floodwater to save a young girl clinging to a branch. He pulled her to shore, left her in the mud, and returned for an elderly man struggling to stay afloat in his long white nightshirt. Again and again he swam in through the branches, broken furniture, shattered wagons and other floating debris, and retuned with bewildered, traumatised people. Eventually, as the fearsome flash flood subsided, he lay exhausted in the mud.

Glancing up at Table Mountain, Johannes ran his fingers over the rope of twisted human hair. It was mostly brown, but there were strands of blonde and jet black – and even streaks of grey. All the surviving women of the town had contributed a lock of hair and woven it into this commemorative watch fob for him.

He smiled. The recollection of that warmth, and of the brave, optimistic and grateful faces of the survivors, displaced the terrible memory of that cold, dark, hellish night. He straightened his spine, releasing the tension that had crept into his powerful shoulders, and strode off into the sunny afternoon.

The facts: The Northern Cape town of Victoria West was devastated by a flash flood in 1871, with more than 60 fatalities. Johannes Buyskes arrived at the town in time to save a number of people, and Rainie Dodds was drowned in her wedding dress that she had been trying on when the town was engulfed by a four-metre-high wall of water.

The artefact: In Victorian times, human-hair fob chains were made either as romantic gifts to loved ones, or from the hair of recently deceased people to remember them by. As far as I know, this may be the only instance of a collective human-hair watch fob. The one on display in the Victoria West Museum is not the actual one given to Johannes Buyskes, but it is an authentic Victorian piece. The watch fob is part of a general display on the history and material culture of the town.

The museum: Victoria West Regional Museum (053 621 0413) also has a section on Karoo fossils, particularly fish fossils, and a large collection of historical guns.

The moral: Don’t build on flood plains.

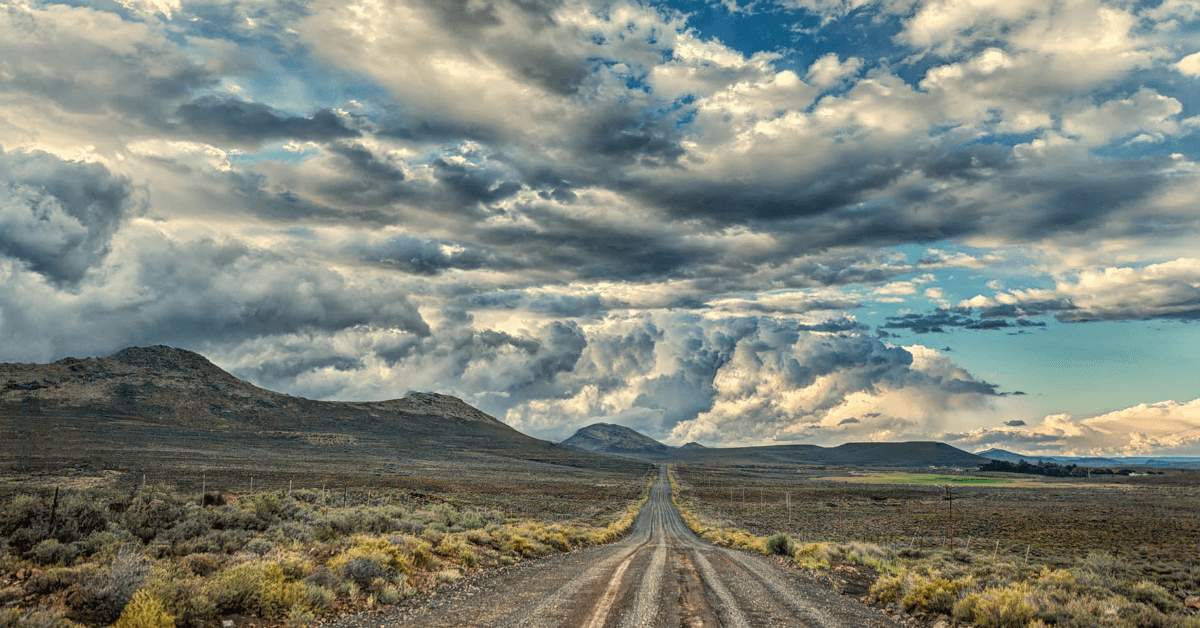

Why there are flash floods in the Karoo

The Karoo is a dry, semidesert region with infrequent rain and dry river beds – river beds that may not see water for decades. When it does rain, however, it can rain hard. Water levels can rise very rapidly and, because the rivers are usually dry, the channel may be blocked, so the floodwaters tend to build up behind all manner of barriers before breaching them and continuing as a higher and faster wave, pushing huge trees, rocks, fences, bits of buildings or even animals and people down the river bed and flood plain at terrifying speed. Such floods occur in the Karoo at irregular intervals once or twice a decade, but most are not as destructive as that of 1871. In fact, while flash floods are always dramatic, they are dangerous only when they run through populated areas. After the flood described in the story, Victoria West suffered another one in 1909 so, in 1918, they built a dam that they hope will prevent a recurrence. So far so good.

The best documented and most devastating such flood in South Africa was the 1981 Laingsburg flood that claimed over 100 lives, and destroyed more than 180 homes. (There’s a whole museum in Laingsburg devoted to this flood.)