Advertisement

‘Pergola’ might be the one word more than any other in the language of gardening that gets us thinking of hot, quiet, lazy Mediterranean afternoons heavy with the scent of newly cut grass; afternoons filled with family and Chianti, fresh basil, and rich, ripe tomatoes anointed with the thickest, finest olive oil.

Consider this passage from The Lady in the Palazzo: At Home in Umbria by Marlena de Blasi: It was Don Paolo’s birthday and all the people of the village were gathered in the piazza to celebrate him. The band played, the wine flowed, the children danced, and, as he stood for a moment alone under the pergola, a little girl approached the beloved priest.

‘But Don Paolo, are you not happy?’ she asked him.

‘Of course I am happy,’ he assured the little girl.

‘Why, then, aren’t you crying?’

Even more than the ‘piazza’ in there, it’s that ‘pergola’ that makes Ms de Blasi’s passage so evocative, that places the scene so perfectly in its own particular part of Italy – and, since it puts everything into a cultural context, too, it even helps us understand the little girl’s question.

Make the pergola African again

Italy isn’t the only country in the world where long summer afternoons tend to

become hot and lazy, and, while the word ‘pergola’ is Italian, they probably didn’t invent it. It’s more likely an African original. Proof of this comes from the world’s oldest known garden plan, which dates back to Egypt in about 1400 BCE, and which shows that visitors would have entered the garden of one of the grandees at the High Court of Thebes through … you guessed it … a sheltering pergola.

And that makes sense. The pergola’s welcoming shade would’ve lifted the simple act of entering the garden into one of entering a cooling piece of paradise. Although, to be sure, pergolas would’ve been more than just entryways for the Egyptians: they’d have been invaluable supports for many of the crops they considered irreplaceable – grapes, for example, or pomegranates or figs.

Advertisement

But what is a pergola?

A pergola is almost any open-sided structure in the garden that’s designed to support plants that provide shade. In early European gardens – in France in the 1400s, for example, or during the Italian Renaissance of the 17th century – pergolas usually consisted of two parallel lines of solid, classical stone columns that supported a latticework of wooden beams that, in turn, supported fruiting vines or decorative creepers. A green tunnel, in other words, often covering a pathway that led, perhaps, to a folly, or a classical pavilion or some other focal

feature.

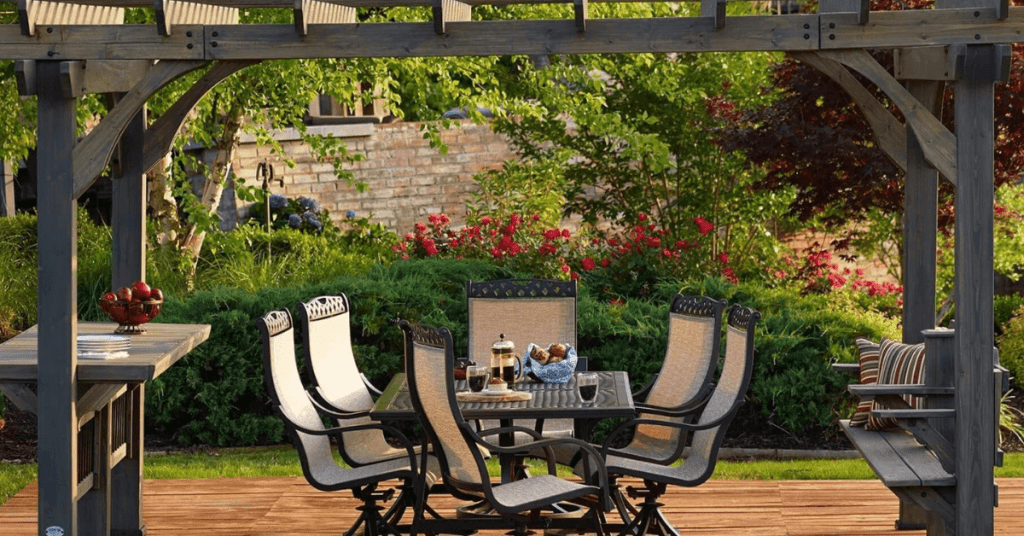

More recently, though, they’ve become far more varied and interesting. Now they cover our pathways as well as our patios, our Jacuzzis, our parking areas, our outdoor lounges and dining areas, and almost any ‘garden room’ that comes to mind. And it’s this combination of being welcoming while at the same time being adaptable to almost any situation in even the smallest patch of sun that makes the idea of the pergola so essentially South African.

(But please, South Africans, it’s a pergola, and not a pagoda, which, beautiful as it is, is really a tiered tower like you might see in parts of Asia. And it’s not a Pongola either, okay?)

Multiple materials

Today’s amazing selection of building materials – steel, stainless steel, aluminium, wood, brick, stone, even plastics or composites – makes building a pergola a pleasure. You can design, literally, whatever you like.

Ideal as links between different areas of your garden, for creating seclusion, for shading an inviting braai area, or for cooling a hotspot that might otherwise have been an uncomfortable, barren corner, pergolas are perfect for adding interest and usefulness to almost any garden, regardless of size. And, since they’re usually less imposing than solid objects like walls or fences, they’re less likely to make your limited space seem cluttered.

If you’re planning a pergola, it’s usually a good idea to begin by deciding what it’s going to support: a lightweight, retractable, horizontal canvas awning probably won’t need as much engineering as a heavy flowering creeper, say, or a hanging hammock for your life-saving Sunday siestas.

Pay special attention to the passage of the sun through your garden – Where’s it hottest in summer? Where’s it absent in winter? – and to the way you and anyone else using the garden are likely to move through it.

Think about it: who can resist an interesting and inviting path that leads to who knows-where? Especially one that’s covered and cool?

Let’s make it our own

Although we usually associate them with plants, not every pergola is covered with creepers, of course, and one particular South African pergola is, quite literally, covered in glory.

Arch for Arch – a nine-metre-high wooden masterpiece alongside St George’s Cathedral, at the entrance to Government Avenue in Cape Town – is a wonderfully original take on this most ancient of garden bowers.

Designed by the Norwegian firm of architects, Snøhetta, together with Johannesburg-based urban designers, Local Studio, Arch for Arch commemorates the life and work of the theologian, anti-apartheid activist and human rights campaigner, Desmond Mpilo Tutu, while also paying tribute to the values of South Africa’s Constitution. Unveiled* in his presence on The Arch’s 86th birthday (7 October 2017 ), it consists of fourteen arched beams that together form a dome, and that correspond to the first fourteen lines of the

Preamble to the Constitution (‘We, the people of South Africa …’).

From that earliest entryway to an official’s garden in Africa’s northernmost country, to this striking modern construction at the gateway to the oldest garden in its most southerly, it’s clear what, while it does look pretty good in those gorgeous Italian gardens, the pergola is most decidedly at home in Africa.

* A second, smaller version of Arch for Arch was unveiled at Johannesburg’s Constitution Hill on the 22nd anniversary of the Constitution: 20 December 2017.

FIVE PERGOLA-FRIENDLY INDIGENOUS CREEPERS

Pride of De Kaap: Bauhinia galpinii

(Calm down. That’s ‘De Kaap’, as in the valley near Barberton in Mpumalanga. Not ‘The Cape’.) Yoh! You’ll need a big pergola for this vigorous, scrambling, clambering, evergreen beauty. But if you have the space – and your garden’s almost anywhere where there’s almost no frost – it’ll reward you with riots of orange flowers in the early summer, and towards autumn, too.

Traveller’s joy: Clematis brachiata

This deciduous climber bears snowfalls of sweet-scented, creamy-coloured flowers with bright yellow stamens (centre bits) in the late summer or early autumn. The decorative, fluffy seedheads remain on the plant well into winter. It’s suitable form most areas of South Africa.

Black-eyed Susan: Thunbergia alata

This quick-growing, usually evergreen creeper (it may be deciduous in colder areas) is indigenous to the eastern and northeastern parts of the country. It tolerates almost any soil type, is relatively frost-hardy and drought-resistant, and doesn’t become rampant even under the most favourable conditions. It flowers almost all year round in warmer areas, and it’s available in colour varieties that range from pale cream to yellow and orange. Black-eyed Susan? They should’ve called it Friendly Susan.

Wild jasmine: Jasminum angulare

This evergreen creeper from the central parts of the country (Karoo, Eastern Cape, Free State, Mpumalanga) produces beautifully fragrant white flowers in summer. It prefers fertile, loamy, composted soil, and does best when it gets at least moderate watering during the warmer months. Withstands moderate frost. It’s a good choice for your pergola if you’re gardening in containers.

Forest grape: Rhoicissus tomentosa

This tendril climber (unlike ivy, it has no suckers to attack your paintwork), with its evergreen, vine-like, hand-sized leaves, would do well on almost any medium-sized to large pergola. It produces small, creamy-green flowers, and purple, grape-like fruits, neither of which are particularly showy. Grow it rather for its handsome, ornamental leaves, which start out soft, furry and coppery, and mature to a satisfyingly deep military green. It doesn’t do well under frost or drought.