Advertisement

The daily news is now dominated by stories of both Eskom and water service failures across the country. The rate of failure is accelerating, exactly as predicted by me some years ago.

At that time, I engaged with several residential estates, warning that system collapse was coming, giving them time to plan for the day that it becomes the new normal. That new normal is now upon us. Subsequently, my own thinking on the roadmap to self-sufficiency has also been considerably refined.

In my professional opinion, municipal collapse is now so advanced that it is unlikely to be halted in the next decade. This means that residential estates will increasingly be obliged to deliver the services that the municipality is simply unable to provide. So, let us unpack this in a logical way, to assist those who now believe that self-reliance is part of the new normal.

Experience has shown me that residents and owners are reluctant to make the investment needed into self-reliance. Therefore, any suggestion made by the trustees, directors or managing agents tends to be negatively received. This is a persistent roadblock to self-reliance because it takes away the opportunity of implementing a phased strategy, thereby reducing costs. All changes in an instant, however, when extended load shedding occurs and water service delivery is interrupted for a week or more. Nothing focuses on the mind of the owner or resident more than a toilet that will not flush.

There are four distinct elements needed to achieve self-reliance. These can be thought of as phases to be implemented systematically over time, commensurate with the appetite for change displayed by the owners and residents. These four elements are:

- On-site storage capability

- Augmentation of supply

- On-site water quality management

- Alternative energy source

The journey must logically start with a lawful decision taken at the AGM that self-reliance at estate level is the desired long-term objective, accepting that municipal and Eskom failure are unstoppable. Unless this decision is taken, all plans to implement self-reliance face the constant headwind of discontent. To assist that decision-making process, owners can be presented with the four-phased plan elaborated below.

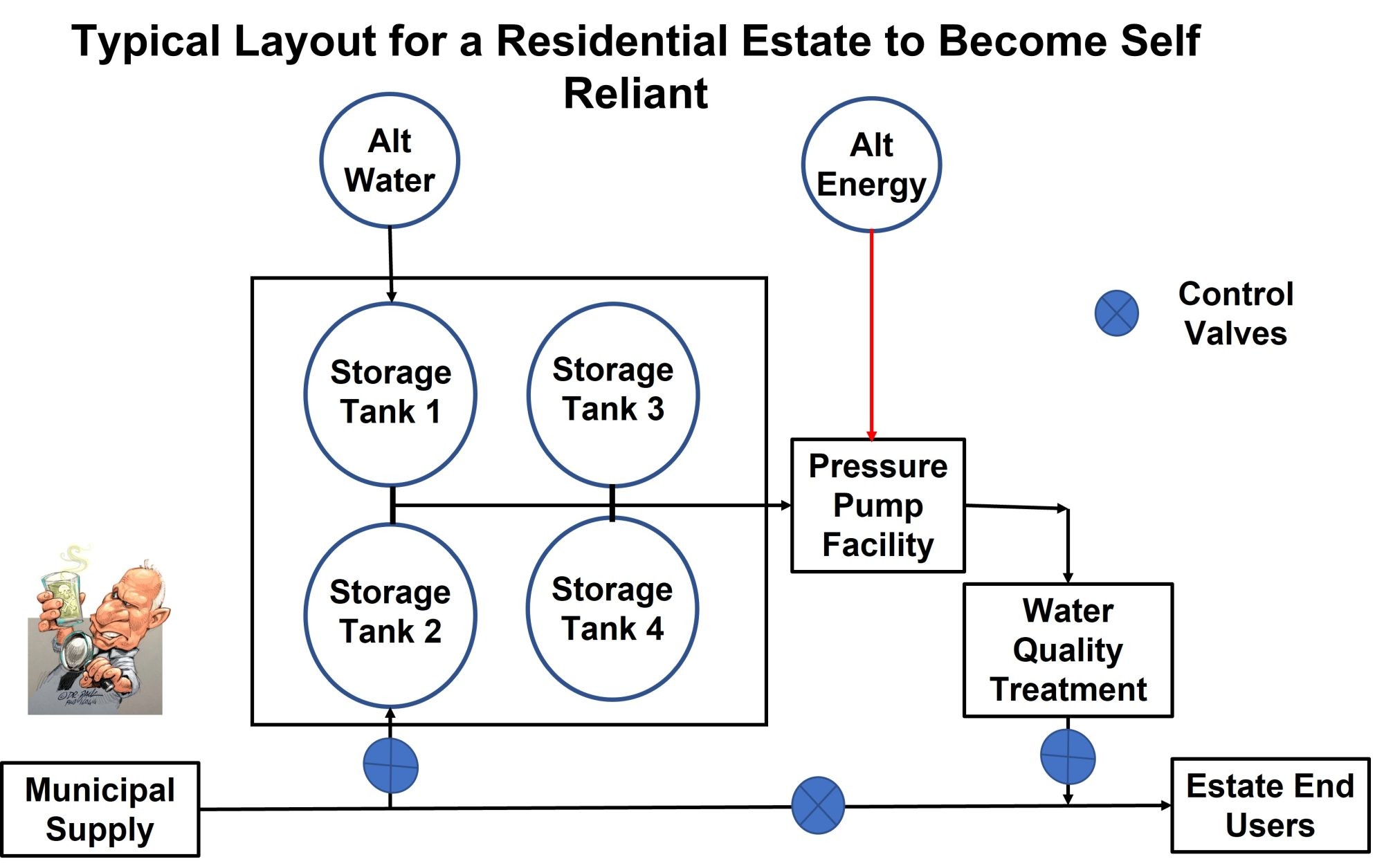

Phase 1 – is the easiest of all to implement, because it is typically driven by the anger arising from municipal water failure for a few days at a time. That shared experience focuses the mind and serves to create a window of opportunity for managing agents, trustees and directors. Service delivery failure is increasing. In the water sector, this is manifest as three distinct elements – long periods of no delivery or reduced pressure, increased failure of wastewater treatment works under municipal control, and deteriorating quality of the incoming water because of sewage contamination in our rivers and dams. Each of these elements needs to be factored into the strategic plan to achieve self-reliance, but at different moments in time. If they are all implemented simultaneously, there is often resistance from the owners, simply because they are so embedded in their own personal survival that they often fail to understand the complexity of the water issue. Phase 1 is therefore about creating on-site storage capacity. This requires an open piece of land, preferably close to the existing single point of entry for the potable water mains into the estate. The location chosen is important, because the strategic storage must be able to carry at least 48 hours of reserve and it must be fed by the existing municipal main. Water is diverted from the main, into the backup storage – typically a few 10kl tanks as shown in the image – by means of three control valves. Incoming water continues to feed through the main meter, into the estate, but a new line is taken from the main into a tank. That line uses a simple ball valve to keep the tanks full. If the sizing of the tanks is done correctly, then 48 hours’ worth of backup can be created, simply by storage on site. The water, held as strategic backup, is fed back into the mains by means of an automated pressure pump system. The sizing calculation must be done correctly, by taking the average daily consumption and multiplying it by two to give us the 48-hour backup. Once this calculation has been made, it is technically possible to extend the 48-hour period, simply by implementing a policy of reduced consumption when operating in backup mode. This means no garden watering, car washing or pool topping up during the defined period of ‘emergency’ backup supply.

Advertisement

Phase 2 – follows logically but at a distant time into the future. Once strategic on-site storage has been provided, the next step is to find an alternative source of supply. There are many alternatives possible – including rainwater harvesting or water recovery from waste – and each must be evaluated carefully in terms of risk, cost, and benefit. In practical terms, the easiest solution is typically to drill a borehole. Depending on the underlying geology, water is often found, but of varying quality. Groundwater is generally reliable but is not necessarily located adjacent to the tank farm. This is not an insurmountable problem, but as a rule of thumb, the closest drilling site to the strategic storage facility ought to be prioritised. This simply makes the piping and electricity reticulation easier to manage. Borehole water is fed into any one of the bulk tanks, using a float switch to control the pump. A logical decision must be made about the height at which the float switch comes on, because the primary source of water in the tanks is from the municipal main. This means that the ball valve must be set to open first, and only if that fails to keep the tanks full, must the borehole be switched on. To coordinate these two actions, the float switch for the borehole is best located in the same tank as the municipal main ball valve. This implies that the tank being used for this purpose ought to be conveniently located close to the electrical control panel that operates the pressure pump. Once the borehole has been commissioned, it effectively means that the estate is able to function normally for an indefinite period, even if the municipal supply fails completely. This is a psychologically important moment for owners and residents, because the inconvenience of restricted flow, such as limitations to garden irrigation, need no longer apply. Experience has shown that once the first extended shutdown has been endured, the residents become fully supportive of the alternative source of supply (borehole or rainwater harvesting). Until then, many remain sceptical, and often vote against the cost of drilling a borehole and equipping it with a pump and controller.

Once the alternative source of supply is online, the logical issue of water quality management becomes relevant as Phase 3. Borehole water is likely to need some treatment to make it perfectly safe. Here there are two broad options that the managing agent or HOA can adopt. They can decentralise water quality management and leave it to each owner to implement, at their own cost, in their own home. This shifts the burden of cost onto the individual, but such solutions are typically more costly than a single centralised plant. The alternative is therefore to have one centralised water quality management system, installed as an upgrade to the pressure pump plant. Planning for this can be done in advance, during Phase 1, but implemented in Phase 3 to ease the financial burden. This is why comprehensive planning is the most prudent approach.

Once Phases 1–3 have been completed, the next bottleneck becomes energy. Experience has shown that while it’s great to have backup storage, if municipal service failure coincides with an Eskom load-shedding cycle, then the provision of water is constrained by the availability of electricity. For Phase 4 a range of options is available, each with its own cost and benefit, so it’s best to assess all. The simplest solution is to have a small standby generator capable of running the pressure pump and water quality plant. This takes us back to Phase 1, where the siting of the storage tanks is the central issue. If the tank farm is also close to an administrative block or a clubhouse that has its own generator, then efficiency is achieved by sharing an asset. If the tank farm is not close to a convenient central point of alternative energy supply, then a hybrid inverter system that is grid-tied can be considered. This is the least costly option, without solar capability, but with the ability to be upgraded if needed.

In conclusion, the road to self-reliance is not a complex one, and is entirely doable. It is best accomplished after a legally binding decision has been made at an AGM, that the stated objective is self-reliance at the estate level as the desired long-term objective, accepting that municipal and Eskom failure are unstoppable. The decision can be facilitated by presenting a phased plan, embracing the elements noted in this article. Details will obviously be different for various estates, but as a generic solution, each successful programme of self-reliance will embrace these four fundamental elements – on-site storage, augmentation of supply, water quality management and an alternative source of energy.