Advertisement

Rejuvenating inner-city neighbourhoods can be an uplifting, progressive and profitable enterprise, but it’s not as simple as that.

There is absolutely no doubt that inner-city rejuvenation is an indispensable aspect of development in South Africa and, in some cases like Johannesburg’s inner city, the benefits are clear. In others, like Cape Town’s Woodstock and Bo-Kaap, it is necessary to consider whether the cost is not too high. Researchers are therefore anxious to distinguish between ‘gentrification’ and ‘urban regeneration’ or ‘urban rejuvenation’. The Cities Network, for example, specifies

gentrification as a phenomenon in which ‘displacement occurs as a result of capital investment and urban transformation.’

South African urban areas are undergoing significant change, with new spaces for living, working and leisure being created continually. The rejuvenation of neglected and dilapidated spaces is imperative for meeting the demand for housing close to jobs, education and services, and also because inner cities are important for racial desegregation. Inner-city development that is not sensitive to the needs and character of existing residents, however, can destroy

the strong social networks and wholesome community structures that often form in old neighbourhoods. Worse, it can result in economically driven displacement, which makes it even more difficult for lower income families to make ends meet.

In Cape Town’s Bo-Kaap, for example, residents are so concerned about losing their culture and traditions to gentrification that they are engaged in a court battle to stop the construction of an 18-storey mixed use building. They are afraid that it will be the first of a ‘wall of monster buildings’ that will cut off their neighbourhood from the rest of their city. Although gentrification of a sort has been evident in Bo-Kaap for about 15 years, the recent urgency in their protests was sparked by a realisation that the new wave of developments could destroy Bo-Kaap as they know it within the next few years.

Once gentrification starts, say experts, it continues until there is a complete change in the social and physical characteristics of a place. There are different reasons why, when and where gentrification takes place. Partly, it is driven by the rent gap reaching a point at which it becomes attractive to buy neglected properties for renovation or new development, along with demand for both the location and the new facilities that often come with neighbourhood improvement.

Urban regeneration has a number of benefits. It revitalises neighbourhoods, attracts an influx of new amenities, and improves local economic activity. But these are directly linked to its dark side – gentrification. The resultant rise in rents, rates, and property taxes makes living in the area too expensive for the original residents, and forces them to move out of the area – usually to more affordable suburbs far from the city centre. When people live further away from the city centres, they spend more time and money on transport to get to work and school. When people who are not financially strong are forced to spend more of their money in this way, they have less to spend on good food, quality housing and education, and their quality of life drops.

Bo-Kaap

‘We see gentrification as the eradication of the culture and traditions that make up Bo-Kaap,’ Jackie Poking of the Bo-Kaap Civic and Ratepayers Association (BOCRA) explains. ‘The people coming in with the new developments have an income that is way above the income of the present residents, and they live in these buildings that become islands of privilege within a community that consists of working-class families that have lived together for generations.’

Advertisement

Bo-Kaap is not neglected, dilapidated or distressed in terms of both physical and social structures. The buildings are in good condition, and the neighbourhood is thriving. Poking, who is a recent incomer to Bo-Kaap, has merged into the society and proudly describes its old-fashioned sense of community – the kind of community we strive to create in residential estates. Bo-Kaap has a history that is a unique and important part of South Africa’s identity, but it is the very special traditions and culture of the neighbourhood that are what Poking and her colleagues are fighting fiercely to protect. ‘We are not against new people moving in,’ says Poking; ‘the fight is that there is an exclusive rich population buying up our homes, but with no vested interest in our community.’ BOCRA took the City of Cape Town to court this year to halt the construction of an 18-storey building on its boundaries that they say would change the nature of their neighbourhood. Judgement is reserved at time of writing. The development would be a mixed-use retail, office and residential building that would take up nearly a whole city block. When asked if this would not provide much-needed housing for locals, Poking replies that the units are priced way above affordable.

There is a popular belief that if Bo-Kaap is declared a national heritage site, it will be protected from gentrification. The neighbourhood meets the criteria for national heritage site status because of its significance to all South Africans, but has not yet been declared because of opposition from some affected parties. As it stands, it is a provincial heritage site, and this affords it the same protection as a national heritage site.

Ben Mwasinga, manager of the Built Environment Unit of the South African Heritage Resources Agency (SAHRA), explains that heritage legislation limits the nature and type of development that can occur on declared sites. The intention is to protect them from undesirable development. ‘But remember,’ he says, ‘it also limits development by existing home owners, and they also have to get permission for any changes they want to make.’

Any development within Bo-Kaap requires a permit from Heritage Western Cape, the provincial enforcer of heritage legislation, and SAHRA makes a point of providing comment.

Heritage legislation protects a particular demarcated space, but properties in the buffer zone do not require a permit from the heritage authority. In the case of the proposed 18-storey building, because it is on the boundaries of Bo-Kaap, a comment is required from the heritage agency, but not a permit, even though it is considered highly undesirable because it impacts on the historical fabric of the place.

Mwasinga is quick to caution against conflating issues of gentrification with issues of heritage protection. For a start,

heritage status does not limit property rights, he says: ‘There is nothing that stops someone from selling their property.’ Heritage legislation also does not affect rates and taxes because those are determined as a function of the municipality.

Finally, heritage legislation protects spaces that are important for cultural use but does not protect the culture itself. Mwasinga clarifies: ‘Heritage will protect the physical fabric of the site from an aesthetic perspective in order to protect the use of the site.’ For example, it will not dictate how, where – or even whether – Bo-Kaap residents observe the traditions of Ramadan, but it will protect a square that is used traditionally for neighbourhood

iftaar (end-of-fast) gatherings.

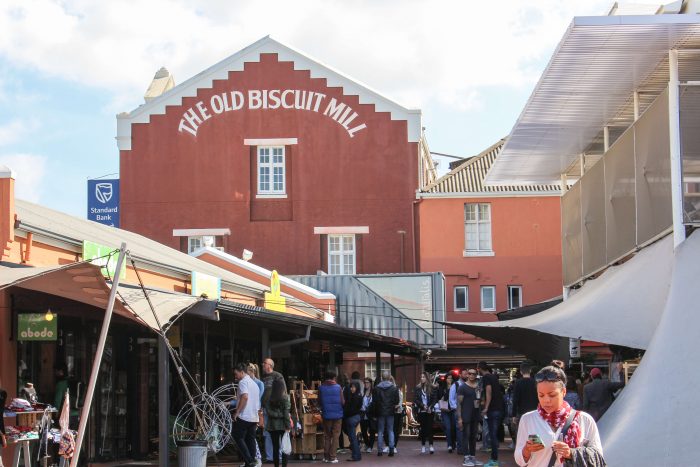

Woodstock

Urban rejuvenation can in fact empower the original residents of a neighbourhood even while meeting the demand for new affordable and upmarket housing and commercial space. For this to happen, according to Lewin Rolls, who researched regeneration in Woodstock for his masters in 2016, gentrification policies have to favour the poor. He puts forward a number of suggestions for how this can be achieved.

- For a start, he suggests, planners can encourage economic development that supports small businesses, and make sure that public infrastructure benefits everyone living in and using the area.

- State-owned land can be developed for mixed-use and mixed-income development, with a focus on affordable

housing. Municipalities can focus on creating social housing stock and prioritise their development within

shorter time frames. This affordable social housing should be kept as such in perpetuity. Further, social subsidies can be provided for evictees to return to Woodstock when that housing becomes available. - Transparent, inclusive planning and zoning will help to make sure that the needs of low-income residents and

small local businesses are not disregarded. Therefore, he emphasises, all stakeholders have to be included in

decision making about the maintenance and improvement of infrastructure, so that ‘officials, residents and NGO representatives engage in a process of co-designing the future of Woodstock.’ - Rolls also suggests broadening the Urban Development Tax Incentive to focus on economic development and support for small businesses, and incentivising the development of social housing. In addition, he suggests applying a Woodstock Local Area Overlay Zone that ‘allows the municipality to apply specific development controls that reflect local circumstances and to encourage development that supports the local economy.’ Opening the streets to local markets and community celebrations would go a long way towards building a new sense of community – or reviving an old one.

Change is the only constant

Cities are always changing, but for cities to be developed in a just, equitable and democratic way, rejuvenation has to protect the people who are already living in the inner city, and make sure their needs are provided for in the course of development. As Rolls writes: ‘The city should be one that is accessible to all, where neighbourhood development creates equal opportunities for all, thereby allowing for the social and economic growth for all who reside in or have access to the city, not just the affluent minority.’